Cordage is the most underrated tool in your ultralight kit. Learn how to rig, repair, lash, and hang with nothing more than a few feet of line—saving weight while staying prepared.

Read MoreWanderlust in the Blue Ridge: Top 10 Hiking Trails in Asheville, North Carolina

This expanded guide covers the top 10 hikes near Asheville, North Carolina, including trail length, difficulty, drive time, and what to expect. Ideal for day hikers and weekend explorers.

Read MoreFloating Through the Forest: Pros, Cons, and Tips for Hammock Camping

Hammock camping is lighter, cleaner, and surprisingly comfortable. This guide explains what works, what doesn’t, and how to get the setup right.

Read MoreBest Campsites Near Waterfalls in Western North Carolina

Western North Carolina offers an outdoor enthusiast’s dream: hundreds of cascading waterfalls paired with spectacular camping opportunities. Transylvania County alone, aptly nicknamed the “Land of Waterfalls,” boasts over 250 waterfalls, making it a must-visit destination for nature photographers and adventure seekers.

Read MoreBrevard’s Forest Ghosts: A Journey into the World of White Squirrels

Brevard, North Carolina is home to a rare sight: white squirrels. These striking animals aren’t albinos but leucistic gray squirrels with snowy coats and dark eyes. This article explores their unique history, where to find them in town, and why they’ve become a symbol of local pride and care for wild places.

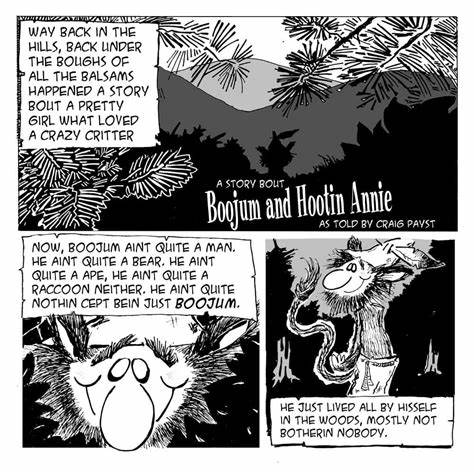

Read MoreWhen Man and Mountain Merge: The Tale of Haywood County’s Boojum

Discover the captivating tale of the Boojum, a cryptid that seamlessly weaves folklore, mystery, and nature into the cultural fabric of Haywood County in North Carolina’s Smoky Mountains. This post explores the legend and the lore, illuminating the deep-seated bond between mankind and the natural world.

Read MoreSenseCAP T1000-E Dog Tracker Guide: Firmware, Settings & 7-Day Battery Life

This in-depth guide shows you how to configure the SenseCAP T1000-E for Meshtastic-based pet tracking. Includes firmware flashing steps, GPS tuning, battery optimization, LoRa settings, mounting options, and troubleshooting tips.

Read MoreLeaf Season in Western North Carolina

The Long Autumn Western North Carolina does not rush into autumn. The change arrives in stages, beginning high in late September and rolling slowly into the valleys by early November. The length of this descent is nearly six weeks long and is what makes the region rare. Most places offer a brief two-week window of […]

Read MoreThe Night Sky above the Blue Ridge

The mountains of western North Carolina hold a secret that urban dwellers rarely encounter: darkness. True darkness, the kind that existed before electric lights carved up the night. Drive three hours west from Charlotte, past the last strip mall and gas station, and you’ll find yourself in a place where the Milky Way stretches across the sky like spilled sugar.

Read MoreWilderness Fishing in Western North Carolina: Traditional Techniques for Long-Term Food Security

Western North Carolina’s mountain streams have sustained traditional fishing practices for thousands of years. The Cherokee developed sophisticated methods using handmade gear, natural baits, and deep ecological knowledge that modern practitioners can learn today. These time-tested techniques work consistently for long-term food security, from crafting hooks from bone and thorns to reading water like ancient texts. Brook trout, rainbow trout, and smallmouth bass respond to seasonal patterns that wilderness anglers can exploit with patient observation and traditional skills.

Read More